|

|

| |

| Ada

DiNardo: One Woman’s Journey to Canada |

| By

Fiona Story |

| Ada

DiNardo never expected to come to Canada. Ada grew up on a farm in the

tiny town of Roccamontepiano,

in the province of Chieti, with her two younger brothers Rocco and Ettore

and younger sister Maria. Her parents planned for her to marry, stay

in Italy and raise a family of her own.

In 1939, she followed that plan and, at the age of

20, she married Palmerino DiNardo, a man living in the same village.

One year after their marriage he went off to fight in the Second World

War and never came back. He was proclaimed missing in action.

Sixty-one years later, sitting at her son’s

dining room table with her feet barely touching the ground, Ada says

she decided to move to Canada due to the conditions of life offered

by post-war Italy.

“I wanted something better, a better life,”

she shrugs.

|

|

So

Ada changed her parents’ plan. She turned down an offer of

marriage from Rocco DiNardo, another soldier in the war from her

village. And in 1949, Ada wrote to Palmerino’s cousin, Rosa

Tiezzi, in Canada. Rosa applied for Ada to immigrate and work as

a maid in her house, even though there was no room for Ada.

“In

those days the immigration bureau would go and inspect the house

where you’d be staying,” says Ada. “Rosa showed

them her mother-in-law’s room and made excuses and said it

would be my room.”

Despite

her parents’ protests, Ada packed and left for Canada. Using

the money she had received from the Italian government in compensation

for the loss of her husband, Ada paid the 400 lira needed for the

passage to Canada. |

|

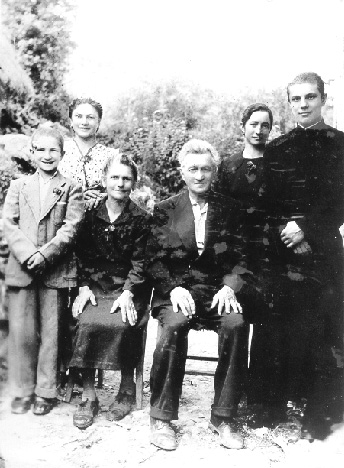

| Ada

DiNardo (second from right) with her parents (sitting) and siblings. |

|

|

“The

boat trip took ten days and I was sick by the second day,”

she says.

It

was on this tiny boat, “Brazil,” that Ada first met

her good friend Rosina Talarico, who was coming to Canada to get

married, as Ada found out in later years. Marriage was a common

method of immigration to Canada and one of the easier ways. Ada

went the hard route.

“Tell

her about the captain on the boat,” her son George prods from

across the table.

Ada

shakes her head and shushes him with her hand, proclaiming that

it is not an interesting story. She waits a moment and tells it

anyway. Ada had landed her own room on the very tiny boat, courtesy

of the captain who developed quite the crush on her. By the second

night, the captain came to Ada’s room and asked her to marry

him, stating that he hated his job and wanted to settle down with

someone.

“I

told him to leave or I’d scream,” she says, adding that

she avoided him for the rest of the trip.

The

boat docked in Halifax and Ada had to take a 24-hour train ride

to Montreal. When she finally arrived in Ottawa, Rosa Tiezzi brought

her to stay at Franco DiNardo’s home, the uncle of her late

husband.

Ada’s

first job was working in a laundry on Rochester Street. Three months

later, she moved on to the Ottawa Civic Hospital where she steam-pressed

laundry. Ada worked eight-hour days, five days a week and on Saturdays

until one in the afternoon for $18 a week. It was good pay at the

time.

“You

have to work some place,” she says. “I liked it. I was

happy.” |

|

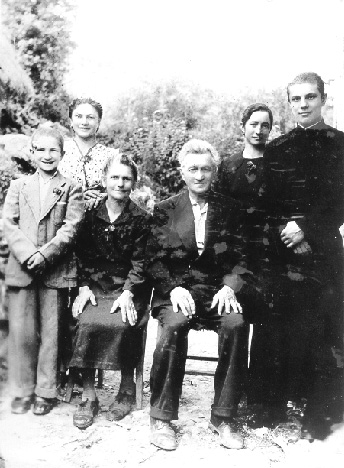

| Ada

and her husband Rocco. |

|

One

year later, she applied for her sister to immigrate to Canada and

Maria eventually came to work at the Civic Hospital too. Some time

after 1953, brother Rocco joined the sisters and the parish priest,

Father Ferraro, helped him get a job shoveling snow at the train

station. Ada’s second brother, Ettore, became a Roman Catholic

priest and is currently serving as the parish priest for an Italian

community in New Jersey.

Ada

did not know any English upon her arrival in Canada and picked it

up one word at a time.

“One

word here, one there. I learned one a day, one tomorrow,”

she says.

She

attended English classes in the evenings at St. Anthony’s

School, however, a man she didn’t know asked her

out one night and this scared her so much that she never went back. |

|

Ada

admits her lack of English impeded her in the workplace when she

was starting out. She was so timid about using the language that

she continued her work without bathroom breaks because she did not

want to ask someone to take her place. After she developed a bladder

infection, she began to use English and even started to act as a

translator between the Italian patients and the medical staff.

Meanwhile,

the Rocco DiNardo from her past had been released from a prisoner

of war camp four years earlier and had made his way back to Italy.

He had gone to Ada’s parents’ house to ask for her hand

in marriage. Again.

“My

parents wrote me and told me,” she says smiling. “I

kinda liked him, you know.”

Rocco’s

entrance into Canada was delayed by two years because Ada’s

former husband had not been declared dead and a marriage to an immigrant

only had a 90-day window. Ada credits Father Ferraro with helping

her to get a death certificate.

In

1954, Father Ferraro married a newly immigrated Rocco DiNardo and

Ada DiNardo at St.

Anthony’s Church.

Ada

laughs, remarking how although she married twice, she has never

had to change her name. George, her eldest son, speculates that

DiNardo is as common a name in Italy as Smith is in Canada.

Rocco

and Ada have been married for 47 years and have four sons: Giorgio,

Giuliano, Italo and Elio. With the exception of Giuliano, who studied

accounting and works at London Life, all are employed in computer

and software-related fields. Ada quit work to raise her children.

Four boys were a handful. Her sons still remember fondly the door

they broke fighting each other, which remains broken today, and

the brand new couch they busted almost immediately after its arrival.

“What

can you do?” Ada shrugs. “Take a stick to them?”

Ada

returned to Italy only once after her arrival in Canada. Twenty-seven

years after she left, Ada took her boys for a visit but said that

Italy had changed and was not as she remembered it. She currently

holds no desire to go back.

“I’m

happy. I have my boys,” she says. “When I was young

I suffered but now I’m here. I’m proud of myself.”

Ada

has eight grandchildren and they flock around her like bees to a

flower, eager to hear her stories. Even in their forties, her sons

still listen intently as she speaks of her life.

Ada

isn’t the only one proud of what she’s accomplished. |

| This

article was originally published in the May 2001 edition of Il

Postino. |

|

| back

to the top |

|